Only Orvilles in the Building

I’m not going to lie, this was a difficult blog post to write. You wouldn’t think so because the Union Hall bill was advertised everyday on the front page of the Kalamazoo Telegraph and performances were reviewed everyday on the back page. Names were given, prices were listed, sponsors were credited, some reviews were more detailed than others. The problem was, I couldn’t get a clear picture in my head of what I wanted to say about it.

Then it occurred to me that without talking about all the local talent that was taking place at the smaller venues, it was all just a data dump. And in a way, this was Union Hall’s eventual demise. More on this in another post. So, in order for you to get a picture of what was going on theatrically and musically at the time of Orville’s arrival in Kalamazoo, I’ve got to talk about the local talent at the smaller halls. And to be honest, that’s where all the good stuff is anyway. Here we go…

Before Orville arrived in Kalamazoo, most lectures, plays and concerts were given at private homes, local shops and downtown businesses. These shops were small, old two story wooden buildings along Main Street. Many had rooms large enough to set up a performance area and to accommodate a small audience. But even before Kalamazoo passed a village ordinance in 1869 against building any new wooden structures, the row of these small, two story buildings on the south side of Main Street between Burdick and Farmer’s Alley, where being replaced with three story brick Italianate style blocks (or buildings).

The ever unique House Block, with its mariner style windows along the roof line, stood at the southeast corner of Main and Burdick. The building next to it was Orville’s future studio at 104 East Main. These blocks, along with the block next to Orville, were all built in 1860. They had an open top floor with a stage at one end. Many of the newly built structures had top floor halls that spanned more than one block (building), with doorways cut through the walls that lead from one block to another in order to accommodate large society meetings. Orville’s building had a door cut between its third floor and the block to the east, which, funny enough, was a bank.

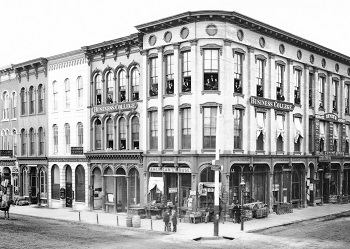

Then along came Union Hall in the mid 1860s. A single block building that spanned 154 feet from the corner of Main Street south along Portage Street, it was built of brick with cut stone framework around the entrance and windows. Individual business spaces were available at ground level with their own street entrances. The actual theater took up the second and third stories and was composed of a stage, a back stage and storage, a main floor and a small balcony. It seated about 600 patrons.

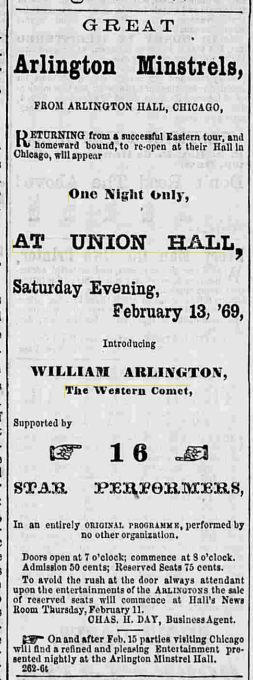

Union Hall was a milestone within the village of Kalamazoo with its population of just under 10,000 inhabitants. The hall immediately started attracting national theatrical troupes traveling on the Michigan Central railway between Detroit and Chicago. At first, it was mainly opera companies (Lotti’s Grand Opera Company, tickets $1.00), minstrel shows (Newcomb’s and Arlington’s, tickets .50 cents) and burlesque (Parisian Follies, tickets .50 cents) that filled the bill. This. at a time when the average laboring family made less than $25.00 per week.

The Ladies Library Association, along with the Young Men’s Library Association, the Y.M.C.A. and the Y.W.C.A. began offering their own lecture series at Union Hall. These included speakers such as Wendell Phillips, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and cartoonist Thomas Nast. Two hundred patrons came by train from South Haven to hear temperance orator, John B. Gough. Season tickets for ten lectures were $3.00 for a single and $5.00 for a couple and were sold at Wortley’s Jewelry store.

As early as 1866, M. George Pearson of Chicago gave a lecture on “Popular Ballad Music of the Olden Time.” Ahh yes, Aerosmith’s ‘Dream On’ is still 107 years away. Tickets for Hall’s Boston Concert on March 23, 1869 could be had for .50 cents, reserved seats went for .75 cents. The concert was promoted by Hall’s News Room. At minimum, George D. B. Hall could collect $300 to pay for advertising, performers fees and hall rental.

This reminds me of when I paid $6 to see bands like the Doobie Brothers, Peter Gabriel and Crosby & Nash at Wings Stadium. Same for The Ark in Ann Arbor where, for a pittance, I saw people like Roger McGuinn, John Hiatt, Darden Smith and Iain Matthews. Too bad those days are long gone.

Anyway, when the locals started utilizing Union Hall, things happened. At some home town vaudeville shows, the hall was so full, some patrons had to sit on the edge of the stage. At times, a group of local band members gathered in the small balcony above and provided the backing music. Pike’s Opera House Minstrels, a local band of performers, promoted their appearance at Union Hall with an afternoon parade through downtown, a common practice for home talent. This company included several actors that Orville would become acquainted with, like Charles Skinkle, steam fitter on cornet and John Bellinger, barber, actor and local pool shark,

Curiously enough, Mr. Jaroslaw de Zielinsky, pianist extraordinaire, from Malone, Franklin County, New York played Union Hall on October 22, 1872. For his line-up with a violinist and two vocalists, tickets were $1.00, available at George D. B.’s News Room.

Next came exhibitions like the Woodruffe Bohemian Glass Blowers, with their Double Acting Glass Steam Engine, of which Mr. Woodruffe was the inventor. This program came complete with a question and answer segment involving the audience.

In 1875, Union Hall received “a new floor suitable for the purpose” of roller skating. The theater portion was built with a level audience floor, so this was entirely possible. I’m guessing they could skate on the stage or in the aisles. Either way, this does not sound like a good idea. The Telegraph reported that the “managers propose to make the new rink a most exceptional place…where all polite people will be pleased to assemble.” Yeah, good luck with that. The reports in the newspapers were painful to read. Patrons didn’t even have ‘Dream On’ to skate to. Tickets were .25 cents, doors opened at 7:30.

As for the smaller halls, like that of O. M. Allen, who owned the dollar store, you could witness and take part in a velocipede (bicycle) exhibition. The best rider received a silver medal. Admission was .25 cents for adults, .15 cents for children. He also booked lecturers and local artists displaying their work.

But most popular were the dances, backed by any combination of local musicians providing the musical portion of the program. By this time Alemania Hall had come along. Arbreiter Hall, Baumann’s Hall and Turnverien Hall all booked lectures, plays and dances. They provided more spacious and more public accommodations for entertainment that used to be given at a person’s home. Musicians that Orville would become acquainted with were James Green, harness maker and cornet, H. H. Everard, sales clerk and trombone. Samuel Born, sign painter and clarinet. John Baker, Edward Crossette and John Early were professional musicians and band leaders, to name only a few.

I cannot conclude this picture of the up and coming local entertainment scene without mentioning “The Peake Sisters.” This sounded so crazy, I had to look it up. First presented by Mary B. Horne on the east coast sometime around 1880 or so, The Peake Sisters were for women what the Keystone Cops and slap stick were for men.

Centered around a group of women in costume, it was a presentation of ridiculous mayhem that included songs and bit comedy. And to connect it to Orville, their presentation at the Y.W.C.A. included him and his band mate Roland Knight, providing music. Roland’s sisters, Della and Inda Knight, were also part of the performance. I would’ve loved to have seen this.

As it happened, Union Hall couldn’t keep up with the times, even with renovations and various changes in management during the 1880s and 1890s. The floor was still level, while new theaters were being built with floors that slanted toward the stage giving the audience a better view. It was also limited by its configuration, even with a remodel that provided seating for about 1200 ticket holders. Union Hall couldn’t compete with the new Academy of Music, built on Rose Street in 1881, by performers, for performers, with all of its modern conveniences and design.

In 1900, the worn out theater was removed, a third floor was added and all was made into office rentals. The building itself still exists with a new facade and is owned by the Gilmore’s. There’s a photo from 1960 in the collection of the Portage District Library which shows its original keystone entrance. Very cool.

I cover much more of the music scene during Orville’s time in my book. Kalamazoo had a thriving local pool of amateur and professional talent and an enthusiasm that is hard to convey in such a short blog post. I hope I have expressed what Union Hall did to give rise to a greater engagement of it’s citizens. Now if you’ll excuse me, I have a date with a violin and some historical newspapers.