Only Orvilles in the Building

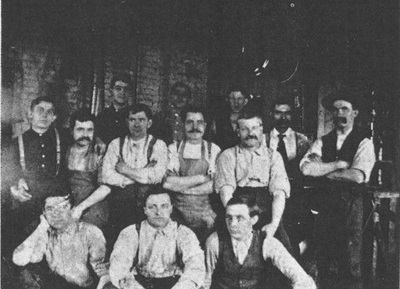

Julius Bellson remembered George Altermatt. He included a group photo of production workers in his pamphlet, “The Story of Gibson.” It’s a toss-up whether I use his original title from 1973 or the title from the later company version, “The Gibson Story.” George is in the middle row, third from the left. This photo was probably taken between 1907 and 1909, just before the company moved to Harrison Court. The guy in the front row, third from left, looks a lot like Neil Kievit, which means that may be his father, Cornelius. If so, that would date the photo to 1909.

Another worker is Eugene Weed, back row, third from the left, although it’s hard to see him because the background is so dark. I’ll see what I can do with that in PhotoShop. The foreman-looking guy with his arms crossed is probably Victor Kraske who came to Gibson from the Barrows/Waldo company in Saginaw around 1907. Jack French has seen him (read the “Rumors” blog entry).

George Altermatt, one of the first Gibson employees, was descended from cabinet makers. And so he was one as well. He married in 1896 and in 1901 is listed in the Chicago City Directory for the first time as an instrument maker. Many local Chicago factories produced brass instruments. One that worked in wood was Lyon & Healy on the corner of West Randolph and Bryan. This factory was in addition to their retail store downtown. But it’s yet to be discovered if that’s where George got his start.

When the articles of association of the Gibson Mandolin-Guitar Manufacturing Company Ltd. were signed into existence on October 10, 1902, the company had no factory, no tools or machinery, no raw materials inventory and only one production employee…Orville. By mid December, the company was still waiting on the last of the production machinery.

For this reason, I seriously doubt that there are any 1902 “company” made instruments. Only Orville’s and kindling. Gregg Miner and I have had conversations about this and agree that the learning curve would have been far too great for a cabinet maker to produce any saleable instruments, even seconds, in the waning days of 1902. Even in 1903, any new employees were probably producing just as much kindling as they were saleable mandolins.

Very early in 1903, Orville was finishing up two instruments, an F style mandolin and a harp guitar, for the Mexican Musical Monarchs. He also has to complete 25 instruments for the Gibson exhibit at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis by next June. It’s doubtful that he had much time or patience for any extensive vocational training throughout 1903. The company made it through their first year by the skin of their teeth..

The Gibson company placed want ads for production workers in newspapers around the Midwest. Kalamazoo had carpenters and craftsmen that made wood and glass retail cabinets, wooden sleds and stair cases, but no one who was skilled at scraping wood to within a 1/16th of an inch fit.

The earliest want ad I’ve found is in the Chicago Daily News in 1903. As you can see, they were looking for two men who could do inlay work and one man for polishing. This would obviously free up Orville’s time for the core production work, It also tells us that the company was doing their own inlays right from the start.

Another want ad appeared, again in the Chicago Daily News, in October of 1903. The scan is not that great, so I’ll transcribe it here.

“FINISHERS WANTED—SIX FIRST-CLASS ALL- around men, two brush men, who understand staining and flowing; four rubbers and polishers to work on mandolins and guitars; preference given those who have experience on mandolin and guitar work. Gibson Mandolin-Guitar Mfg,, Co,, Ltd., Kalamazoo, Mich.”

Evidently, they didn’t get the polisher they wanted. The World’s Fair deadline is looming, so now they want six workers. They’re now making a point to ask for those with previous experience. You have to remember, of the five founders; Williams, Reams, Adams, Van Horn and Horbeck, none had any experience whatsoever setting up or running a factory.

I’m sure they looked to Orville for that as much as their egos would let them. I’m looking at you, Sylvo. Only Syvo Reams and Leroy Hornbeck had run any kind of a business at all. Sylvo owned and operated a retail music shop in town and Leroy, an attorney by trade, developed real estate. They needed all the experienced help they could get.

In 1903, maybe after seeing one of these want ads, George and Agnes Altermatt moved to Kalamazoo with their two young sons, George jr., 3 years old and Charles, 1 year old. This is where some questions arise. The Gibson company recognizes his start date as 1905. Wait…one does not up-root his vulnerable young family to go back to a job as a mere cabinet maker in the village of…where? Kalamazoo? You’re joking, right? Is that even a real place?

George could have kept doing cabinet work back in Chicago, probably with seniority. Ok, so what did he do in Kalamazoo for the two years prior to 1905? There were opportunities for cabinet makers in town, but he had moved on to instrument making, a much more detailed and skilled profession. Did he start at Gibson and Orville pissed him off so he quit and then came back? I can see that happening.

In December 1903, Gibson placed this want ad in an Indianapolis newspaper. Four benchmen for pearl and celluloid inlay and two for stringing. Either they didn’t get the inlay workers they wanted from the other ad or Orville is in need of help with those World’s Fair pieces…or both. Possibly being aided by George Altermatt. Regardless, Lewis Williams set up the exquisite Gibson display in St. Louis by July of 1904…covered in my book.

George and Agnes raised their sons in Kalamazoo. Their boys started out at St. Augustine’s School downtown. Both George jr. and Charles sang and played piano at their Vine Street School where they ended up. What? No mandolin? George jr. was employed at the Kalamazoo Stationery Company at the time of his marriage in 1923. Charles became a career Navy man, married in 1926 and lived out the rest of his life in Los Angeles. So there was no following in their father’s footsteps.

George moved with Gibson from the Exchange Place factory, to the Harrison Court Building that was large enough to house the company for about 5 minutes, and on to the factory on Parsons Street. The whole time that location was eating up the surrounding blocks thanks to some shrewd….real estate dealings. Imagine Indiana Jones’ nod when he says, “Trust me.” Models changed, innovations were made…and banjos, god forbid. I’m kidding. Brother #1 plays banjo. Materials came and went, time cards were punched, snow was shoveled, train cars were unloaded.

Born in 1869, George Sr. was too old for the draft for World War I, so he worked at Gibson continuously through that era. He retired in 1940 at the age of 71. He would have been 66 years old when the Social Security Act was signed into law. At least the company let him stay long enough to claim what little benefits he had earned in those 5 years.

George Altermatt’s great grandson comes in to the place where I work. He gave me this scan of a photo of him, taken by the company at his work station at the Parsons Street factory, upon his retirement. As you can see, if you have a Gibson violin…we know George probably had a hand on it.

.

I write extensively about these first 13 or so Gibson company employees in my book. Some stayed, some did not. I’m grateful to be able to tell a bit of George Altermatt’s story. He was an important part of the early success of the company and on in to 1940. I’m sure many Gibson followers would’ve liked to be able to sit down and talk with him, maybe as much as they would Orville.